Wait a Minute... Am I a Film Bro?

Can a working director accidentally become the guy he never hired? Can you love cinema without becoming a cliché? Am I being silly and maudlin?

I had to take a minute.

And by “a minute,” I mean I had to step away from FilmStack for a bit—a blossoming online community that I truly believe is genuinely trying to save cinema. Not through discourse-for-discourse’s-sake, but by building something together. A collective. A movement. A beautifully chaotic thread of obsessions, disagreements, and spreadsheets.

And yet, in the middle of all that love and cinematic idealism, I found myself having a dumb, borderline melodramatic spiral.

“Wait. What if I’m a Film Bro?”

Not ironically. Not performatively. Like—actually.

Before anyone else even weighed in, Maria—my wife, and the person who knows me better than I know myself—just rolled her eyes and said, “Absolutely not.”

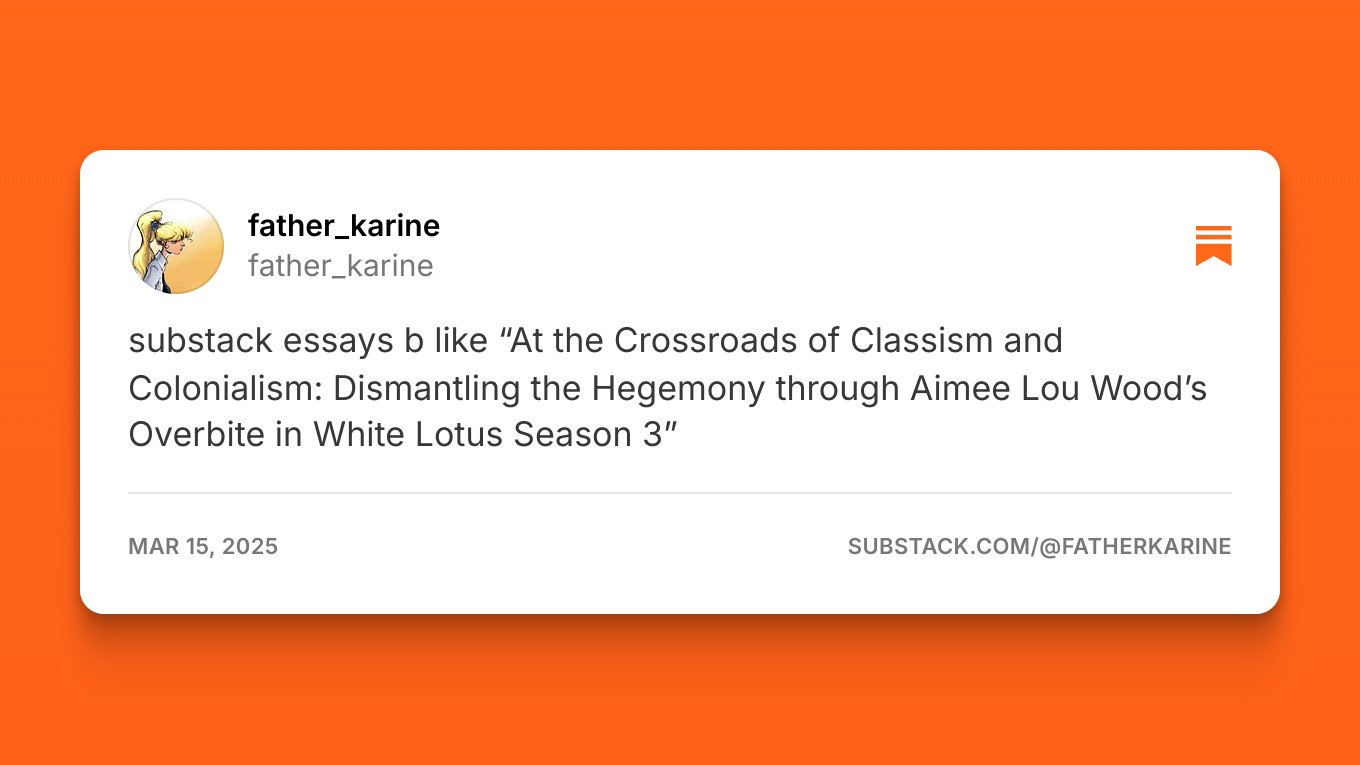

I know. Substack isn’t the place to workshop your identity crisis. It’s a sacred space for 1,000-word screeds on how to save the dying moviegoing experience alongside respectful arguments about Ryan Coogler giving us every aspect ratio known to man in his latest film, Sinners.

But something about skipping posts by amazing writers—on purpose—while feeling a low-level buzz of taste fatigue, and subconsciously scrolling past yet another Substack think piece I couldn’t emotionally commit to.

Yeah. I cracked a little.

Substack sometimes gives me flashbacks to the Clubhouse App during peak pandemic lockdown—all those late-night audio rooms where we planned short films and dreamed up collectives for the post-COVID world. Some collaborations were brilliant. Most are now filed under “cautionary tale.” Here’s hoping Substack doesn’t follow the same arc.

Then I clicked on

’s “I Don’t Want to Read Your Think Piece” thinking it’d be a nice little scroll. Instead, it politely escorted me to the mirror.1Because I got it. I’m on Substack and I didn’t even want to read my own post drafts.

Is that burnout? Cultural detachment? Or am I just becoming the kind of person I’ve spent years avoiding?

Someone writing “deep” reviews into the digital void while skipping everyone else’s work.

So, naturally, I did what any self-aware Xennial filmmaker with two sisters and too many feelings would do—I dropped it on our next FaceTime group chat.

My oldest sister was calling from the Philippines, mid-reunion glow. She’d flown out with my mom to visit relatives, and they brought along my 93-year-old Lola (that’s Grandma in Tagalog), who’s still sharper than most studio executives I’ve met. We were catching up on family stuff—travel logistics, what Lola was eating, the usual—when out of nowhere, like a record scratch in the middle of a ballad, I dropped the question:

“Do you guys think I’m a Film Bro?”

My youngest sister, who’s currently thriving in the music industry, was posted up at some Larchmont café where the salad had its own social media presence. Her partner sat across from her, stylish and unbothered, sipping something expensive and green. I was in my office, surrounded by open tabs, film equipment I hadn’t put away since my last shoot (months ago), and what can only be described as a classic Xennial spiral—nostalgia, tech fatigue, and an unearned sense of cinematic doom.

They laughed. Not unkindly. Not cruelly. But that very specific sibling laugh—the one that says, “You’re spiraling, but we love you. Please continue.”

Let’s break it down.

A Film Bro:

Treats Letterboxd like scripture.

Quotes Pulp Fiction in earnest.

Thinks Drive is underrated.

“Just doesn’t get” Lady Bird.

Uses “auteur” as a flex.

Weaponizes taste as identity.

Here’s some Film Bros gently spiraling about their Film Bro-ness… and coping by leveling up.

Being a Film Bro isn’t just about taste—it’s about policing everyone else’s. It’s gatekeeping in a Letterboxd disguise. It reeks of mansplaining, of judging someone for how they love a movie instead of celebrating the fact that they love it at all. And the worst part? When they talk loud enough, the rest of us get lumped in with them.

They love film. But more than that, they love the performance of loving film. They don’t invite you in—they make you earn it. And for most of my life, I tried to be the opposite. But suddenly, sitting there mid-scroll and mid-salad-envy, I wasn’t so sure.

I brought the question to my colleagues.

My production designer—a delightfully sharp, no-filter friend who tells it like it is—didn’t even blink before he served his diagnosis:

“You love movies and you’re a man. So yes, you are.”

Brutal. But honestly? It was giving spoken-word slap.

Actors—bless their kind, emotionally literate hearts—were more generous.

One of them, barely looking up from their phone, deadpanned:

“Enrico, you have an empty Letterboxd account. The only movie you like is your own.”

Which—okay. Ouch. But also: fair.

Because isn’t that the most Film Bro thing a director could possibly do? Zero activity. One film. Total ego. It’s giving Seth Rogen from The Studio. Plenty of bravado, not a shred of self-check. A résumé written in neon. If I ever start describing my own film as “a vibe,” please stage an intervention—with soft overhead lighting and a strong sense of mise-en-scène.

In a moment of peak self-awareness—and peak cringe—I turned to the one entity I’m both fascinated and slightly unnerved by: AI. Which, frankly, is low-key unsettling. Between her, my wife, and my sisters, I’m not sure I have a single delusion left.

She—yes, she—dug through all things me, including that time I absolutely torched The Brutalist.

Hot take? Definitely. Film Bro behavior? Possibly. Most popular thing I’ve ever written? Oh, without question. See for yourself.

Ironically, my Brutalist takedown is still my most popular post. Not because it was mean—but because people love when someone finally says, “It’s okay to feel nothing when you were told to feel everything.”

Look, I know asking AI for emotional validation is a choice but I was in too deep. She did her homework and somehow, she brought me to a thoughtful conclusion. She reminded me that I don’t write to win. I write to feel. To connect. To let people in. And maybe that was true.

Still, I couldn’t shake the doubt.

So I turned to someone who knows me even better than my AI. I went back to my little sister again. This time, just her.

We were on one of our usual FaceTime—she in her Larchmont café, casually deconstructing a pastry that looked like it had a publicist, me sitting in my office surrounded by film gear.

And out of nowhere, I asked her again—this time quieter, more honest:

“Do you think I’m a Film Bro?”

She didn’t miss a beat. No dramatic pause, no long speech. Just this:

“Kuya, you’re not a Film Bro. A Film Bro has mostly surface-level knowledge of movies. You’ve made two features. You direct countless things. You’re more than that.”

It was the kind of offhand comment she probably forgot five seconds later. But I didn’t. Because in that moment, she reminded me of something I already knew—but needed to hear out loud.

In Filipino culture, Kuya means “older brother.” But it’s not just about birth order—it’s about care.

Maybe I’m not a Film Bro. But perhaps, a Film Kuya?

A Kuya isn’t loud. He’s steady. Protective. Sometimes annoying. Often embarrassingly earnest. He listens. He shows up. He makes sure you’re fed and that your lighting setup won’t cast a weird shadow on your coverage.

Being a Film Kuya means saying, “I love this movie—and if you don’t, that’s okay. Let’s talk about it.”

It’s about making space for other voices. It’s inviting, not intimidating. It’s watching your little sister’s eyes light up when she talks about Wicked, even if your brain wants to pivot to Roger Deakins.

And honestly? That’s who I want to be in the film world. Not the guy with the list of directors you should know. But the one who asks, “What did it make you feel?” The one who creates stories that leave the door open. That welcomes you in. That doesn’t just show you a world—but holds the camera steady while you walk into it.

And maybe part of why I even had this crisis in the first place—is because I love movies that much. I always have. Ever since my late father took me to a triple feature of the Indiana Jones films and I saw Raiders of the Lost Ark on the big screen for the very first time. That was the moment. That was when cinema stopped being something I watched and became something I wanted to make.

And in a world full of cinematic poetic justice, the last movie we ever watched together on the big screen—my dad and I—was Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. His name was Enrico Sr. I’m Enrico Jr. And “Enrico” is the Italian form of “Henry.” He has always been my Henry Jones Sr.—in life, and in all my cinematic endeavors. He was the reason I fell in love with storytelling in the first place. And he remains the quiet presence behind every frame I’ve ever tried to hold steady.

I love movies so much, maybe sometimes my overzealousness reads like I’m trying too hard. Or doing too much. Or chasing the feeling instead of just sitting with it.

But if there’s anything I’ve learned—it’s that loving something deeply doesn’t always look cool. Sometimes it looks messy. Sometimes it spirals. Sometimes it writes an entire Substack post trying to prove it’s not a think piece.

That’s the filmmaker I want to be. A Film Kuya. And maybe that’s enough.

Disclaimer

I told myself this would be more of a personal reflection, less essay-length spiral. Something breezy. Grounded. Casual. I just followed Emily’s prompt.

So if this feels like a think piece—it probably is. If it feels like I’m being silly—it's because I am. Maybe. Heartfelt? Accidentally, trust me.

But hey—there are far worse sins than asking the internet if you’ve accidentally become a Film Bro.

At least I didn’t rate my own film on Letterboxd.

Yet.

It's impossible to read every article you might actually care about on Substack. Even if you stick to just your most central niche - even if you did just movies and scrapped anything about TV - you *still* couldn't read it all. Some weeks I'm here for eveyone else. Other weeks I can barely keep up with whatever workload I've given myself. That's just life in a modenr 24/7 connected global ecosystem. There are too many of us, even as our voices barely move any needles.

That said, I'm with you on regularly taking stock of what I'm writing and why. Think pieces are fine, even hot takes, but sometimes I think Substack writers get stuck in cultual opinion lift-ups or takedowns of every single piece of media or topic. It's great if you think the theatrical experience is superior, but I then often find these same writers failing to find joy in most movies, or it's joy tempered by too many carfeful considerations, and I can't help but think "is this level/speed of consumption a positive for the medium? Or part of the problem?" Whatever the work of creative endeavor - that damn thing likely took years for someone to make. And here we are rattling through them like bullets in a goddamn gattling gun. Cranking out day-of thoughts before hurdle-jumping to the next. While screaming about the sanctity of the theatrical experience. These things mostly do not go together. There can be (and often is) a cognitive dissonance to it all.

There's also the issue of there being a "Film Stack" - a whole subsection that talks about nothing but. Is this a good thing? Film writers only following other film writers and the whole lot circling the whirlpool gravity of their collective togetherness? My own thoughts/doubts recently have turned towad un-nichification. Substack is kind of like an old-school Newspaper. Any mentally healthy individual reads more than one section of a newspaper. And I think it's important we keep ourselves from obsessing over obsessions (and our personal branding.) Be a film Substack, but go read, share, and comment on non-film substacks. Be a full human, even on the internet. The past decade has trained us not to be this, to only be a specific KIND of human when online. And I think we'll always run into doubts that we're "Film Bros" or (in my case) "Wine Snobs" or "Book Dorks" or "Political Junkies" or etc etc if this is the only thing we're herre for, orr the only lens we see anything through.

Substack's size and breadth is intimidating, but also, I suspect, the answer to many previous online environment's ills. We can be more than one thing here. We actually are more than one thing IRL. The better we can mirror our true selves here on Substack, the less we'll face crises of purpose or identity.

Now, if you really DON'T think of anything else or explore anything else IRL, that's it's own issue :P

Really enjoyed this, Enrico; feeling “seen” (as the cliche goes) in ways that were both amusing and, at times, uncomfortably familiar. It’s probably fair to say that much of my adult life has been spent negotiating around the idea of the Film Bro. I studied film at university (UK) in the early 2000s and have since worked as an academic, writer, and podcaster. Like you, I’ve had to navigate shifting trends, evolving platforms, and more than one cycle of crisis in masculinity, both personal and cultural.

I’m currently working on a piece about revisiting American Psycho at 51, having first seen it at 25 (FFS!). That viewing then was filtered through a very different lens, more stylistic awe, less structural critique, and now, it feels like a confrontation with a younger version of myself and the masculinities I once absorbed without question.

I snorted agreement at your criteria for “Film Bro-ness”. And recognised how I’ve consciously tried to avoid, critique or move beyond them. That’s been a core thread in The Cinematologists, the podcast I’ve co-hosted for the past decade. As two male hosts talking about films we regularly articulate an anti-film-broness, and tried to use the show as a space not just for cinephilia, but for interrogating the power dynamics that often shape who gets to speak and how (very worthy, I know)

The concept of the Film Kuya is fascinating. That notion of being the “older brother of cinema”, is a idea that struck such a cord. We’ve talked about that ethos on the podcast quite a bit, and as a film lecturer, it’s definitely the sensibility I aim for when I’m at my best: reflection, enthusiasm, and open conversation, rather than taste performance or just binary categorising.

There was a pang of melancholy too, because I don’t think I ever had a Film Kuya myself. No one to mentor or guide me through my early encounters with cinema. Maybe that’s why I’ve tried to be that figure for others, even if imperfectly.

I enjoyed the balance of irony and humour of your piece, but underneath it, there’s something really honest and affecting about the contradictions and shifting sands of masculinity - particularly as it relates to cinephilia and identity performance. However we define our “cinematic selves,” it’s clear those definitions are as "in flux" as they've ever been. Film-bro-ness is another iteration of territory marking.

Thanks again for this, it resonated.