"The Brutalist" is a Terrible Movie, and Here's Why

Coming from Brady Corbet, a white American director who smugly touts his film as an exploration of 'otherness' in awards season interviews, it feels painfully self-congratulatory and tone-deaf.

**MILD SPOILERS AHEAD**

I wanted to love it. I was ready to embrace it. But by the intermission, I started to have doubts. As it dragged on, my agitation grew. And by the time the credits rolled, it hit me—The Brutalist is a terrible movie.

The Brutalist aims to be a cautionary tale about the perils of chasing the American Dream, but its depiction of the immigrant experience feels inauthentic, filtered through the detached gaze of white American director Brady Corbet. Even putting aside the AI controversy surrounding this film—which is a whole topic in itself, especially considering it explores an artist’s journey—its artificiality and detachment remain impossible to ignore, prioritizing aestheticized suffering over genuine storytelling, as if it's more concerned with its own perceived importance than with crafting an authentic narrative. It’s clear the film isn’t interested in honoring fundamental storytelling virtues—like meaningful thematic contrasts and, more importantly, sheer authenticity. Instead of crafting a film that cements an immigrant’s journey into our psyche, Corbet prioritizes surface-level aesthetics, leaving behind a hollow facsimile rather than a lived experience. Not every immigrant story needs to be uplifting, but this one’s relentless cynicism feels more like an art-house affectation than an honest exploration. Overrated is an understatement.

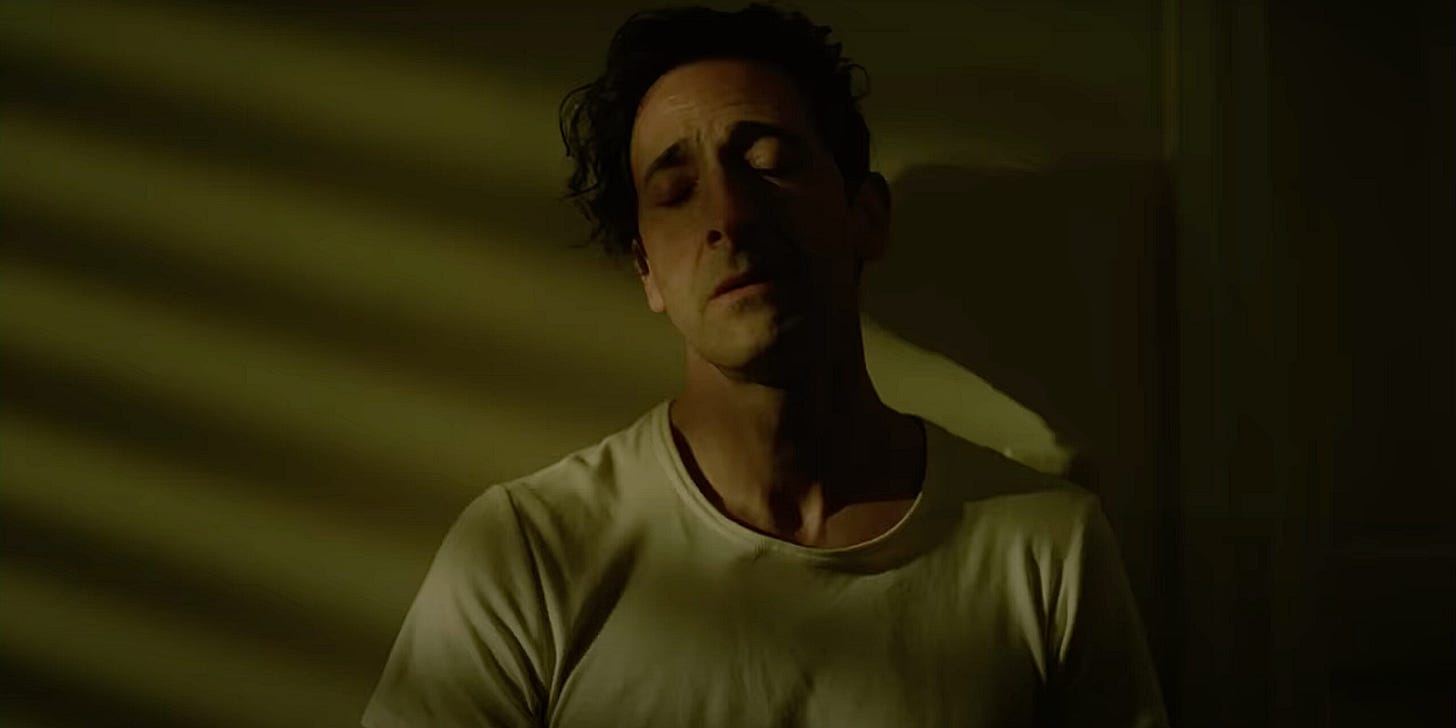

The film follows fictional Hungarian architect László Tóth (Adrian Brody, turning every scene into a personal audition for the world's saddest man competition) as he navigates post-war America, striving to leave his mark in a country that both welcomes and exploits him. On paper, the film presents a compelling premise—one that could have meaningfully dissected the tension between ambition and assimilation. At first, it teases the potential for depth, particularly through Tóth’s assimilated cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola, always underrated), who offers a rare, nuanced glimpse into the contradictions and sacrifices of assimilation in post-World War II America. But rather than exploring these complexities, the film quickly abandons them in favor of self-serious spectacle.

Like everything else in The Brutalist, the characters are mere sketches rather than fully fleshed-out human beings. Take, for instance, Tóth’s supposed confidant, Gordon (Isaach de Bankolé), who serves as nothing more than a shallow embodiment of the 'Black Best Friend' trope. His only traits? A dead wife, a son who is mentioned in passing, and unwavering loyalty to Tóth. Scene after scene, he exists solely to shadow the protagonist—whether bunking in the flophouse, high on heroin in a jazz club, or assisting with Tóth’s increasingly grandiose projects. And yet, when Tóth inevitably casts him aside in a fit of self-loathing, Gordon vanishes from the narrative, never to be seen again. There is no reckoning, no exploration of their dynamic—just another disposable character whose sole function is to elevate the suffering of Tóth.

Toth’s wife, Erzébet (Felicity Jones, detached by no fault of her own, I suppose), appears only in the second act. She’s confined to a wheelchair, embodying every clichéd, fractured female character often found in immigrant stories from a privileged American perspective. Yet another passive figure whose suffering exists solely to amplify the protagonist’s anguish. Look what’s happened to my wife! the film seems to scream, as if reducing her to a symbol of despair is enough to inject emotion into its weak narrative. Ah, the suffering. And don’t get me started on the mute niece, Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy). As if the female characters in this film weren’t already stripped of agency, Corbet doubles down with a character whose literal silence only amplifies the film’s already problematic portrayals. Nothing says “symbolism” like a mute woman existing purely to reinforce the film’s heavy-handed narrative choices.

It’s no surprise that the film has sparked debate, particularly among architects. As The Guardian points out in their article about how architects loathe this film, The Brutalist takes liberties with its portrayal of László's work and philosophy, using architecture as an overwrought metaphor rather than engaging with its real-world significance. The article notes that Corbet “uses brutalism as a stand-in for the immigrant experience, but in doing so, he reduces both to an abstraction.” And that’s the problem. Rather than exploring the nuances of ambition and assimilation, Corbet treats Tóth’s suffering as a blank canvas for his own self-serious vision.

Similarly, The Irish Times article highlights how The Brutalist has been met with frustration from those in the architectural community, but argues that critics “miss the point” because the film “gets genius right.” But does it? The movie treats Laszlo’s story as a tragedy in which his genius is either unrecognized or deliberately thwarted. Yet, as an immigrant myself, I take issue with this framing. The immigrant experience is not one long, unrelenting tragedy. It is filled with struggle, yes, but also resilience, joy, and unexpected moments of connection. The Brutalist refuses to acknowledge this.

Even Armond White—famous for his contrarian takes and a critic I rarely agree with—gets it right in his National Review critique, calling out Corbet’s ‘mulish artiness’ and The Fountainhead-meets-There Will Be Blood posturing. He nails how The Brutalist prioritizes self-conscious grandeur over coherent storytelling. Tóth’s rise is framed as a series of tortured compromises—abandoning his cousin, concealing a heroin addiction, immersing himself in the sexual underground—before striking a Faustian bargain with American tycoon Harrison Lee Van Buren (check out that name!) played by Guy Pearce, who seems trapped in a 1950s villain template—complete with a showy, faux-Transatlantic accent that lands somewhere between an old Hollywood studio head and a mustache-twirling antagonist from a lost noir film. Yet rather than exploring these struggles with depth, Corbet inflates them into pseudo-profound hurdles designed to make the film feel important. By the time Tóth is commissioned to build a monument for Van Buren’s WASP matriarch—a clunky metaphor for his moral decay—the film has long abandoned character depth for hollow mythmaking.

It feels like the richest moments of Tóth's journey happen off-screen—or worse, were left on the cutting room floor (a baffling choice given the film’s lengthy runtime). By neglecting the fundamental storytelling technique of tension and release—an artistic principle found in music, painting, and the greatest films—Corbet reduces Tóth’s journey to a series of disconnected visuals rather than an emotionally resonant arc. In prioritizing aesthetics over narrative depth, the film ultimately diminishes its own protagonist.

This fixation on suffering extends beyond the script—it infects the film’s very aesthetics. Shot in VistaVision, The Brutalist constantly calls attention to its own ‘importance’ with grandiose, self-conscious imagery. Despite the potential for striking compositions, the film squanders VistaVision’s rich detail and expansive frame, reducing it to a series of uninspired, over-composed tableaux that feel more like staid museum exhibits than living, breathing cinema. But as Lol Crawley’s cinematography proves, haughty visuals don’t equal depth. Take, for instance, the upside-down shot of the Statue of Liberty—because nothing says immigrant hardship like a literal inversion of the American Dream. Subtle, right? The film leans so heavily on overwrought visual metaphors that it feels more like an art installation desperately trying to be profound rather than a fully realized narrative. Critic Chuck Bowen of Style Weekly nails it: “The Brutalist wraps itself in prestige aesthetics while offering nothing of real substance, mistaking slowness for significance and bleakness for profundity.” Instead of enhancing the story, its choices scream, Look how artistic I am! Another strange directorial choice occurs in a scene where the steadicam trails a tertiary character—not a main or even supporting one—up a flight of stairs, eventually landing on Tóth, furiously drafting at a large architectural table. Just as the shot finally settles, Tóth inexplicably breaks the fourth wall, locking eyes with the camera. Huh? What does this achieve beyond calling attention to itself, as if technical precision alone justifies artistic choices?

The second-act sequence set in the marble quarries of Carrara, Tuscany aspires to the cinematic heights of Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura, but instead, it plays like 'prestige cosplay'—draped in art-house aesthetics yet devoid of emotional depth. By the time we arrive at this segment, it’s clear that Corbet is more invested in performing his best Antonioni impression than in letting the scene breathe on its own terms. The result is a self-conscious display of style that mimics the languid compositions and existential drift of L’Avventura, but without any of its mystery or substance. What should feel haunting and evocative instead feels labored and indulgent, a filmmaker too eager to prove his influences rather than trust his own storytelling instincts.

The film's running time and the inclusion of an intermission make it seem important, like fancy wrapping for an otherwise empty box of a movie. But the length isn’t the issue—I love long movies. Lawrence of Arabia and The Godfather Part II accomplished far more with their (comparatively) shorter run times, proving that true cinematic weight comes from substance, not sheer duration. Critic Michael Atkinson, in his LA Weekly review, perfectly captures one of the film’s biggest flaws—how it abandons narrative cohesion in favor of a series of disjointed ‘gotcha’ moments. He describes the experience of watching The Brutalist as feeling like you’ve been pickpocketed—Corbet discards crucial elements just to subvert expectations. He likens this to Paul Thomas Anderson’s unconventional storytelling, but where Anderson’s choices feel purposeful, Corbet’s feel arbitrary and self-indulgent, as if he’s subverting expectations just for the sake of it. In film and storytelling, subversion is not an inherent virtue—it must be earned through a deep understanding of what is actually being subverted. Atkinson’s most damning observation? That the film’s most shocking moment—an out-of-nowhere sexual assault—reads like a ham-fisted getting-fucked-by-capitalism metaphor. And that’s the issue: the film piles on bleakness without earning any of its dramatic weight.

Richard Brody, in his New Yorker review, also sees through The Brutalist’s empty ambition, calling out its lack of genuine insight and over-reliance on aesthetic posturing. He critiques the film arguing that it ‘fetishizes suffering rather than illuminating it.’ When even a New Yorker critic—who often appreciates art-house cinema—finds the film frustratingly hollow, it speaks volumes about how The Brutalist fails at its own lofty ambitions.

Jeffrey Wells, in his Hollywood Elsewhere review, also criticizes the film’s lack of narrative momentum, stating that The Brutalist “coasts on its aesthetics but goes nowhere.” I couldn’t agree more. Its characters stagnate, its story drags, and by the time we get to the epilogue, nothing feels earned. The result is an exhausting experience that leaves little impact beyond frustration.

This is where Brady Corbet’s self-importance become impossible to ignore. The film’s fixation on artistic autonomy—who controls the work, who dictates its legacy—feels like a thinly veiled reflection of Corbet’s own triumph in securing financing and completing the film on his own terms. It’s a self-mythologizing exercise, one that has bolstered Corbet’s reputation, and he only reinforces this in interviews, repeatedly aligning his own supposed suffering artistry with that of his protagonist. This self-mythologizing isn’t just off-putting—it’s borderline insulting. For an immigrant watching Corbet equate his artistic struggle to Tóth’s journey, it feels less like self-reflection and more like self-indulgence. This is precisely what makes the film feel so fundamentally detached and inauthentic.

And it’s not just me—friends, family and colleagues I’ve spoken to who’ve seen the film aren’t exactly raving about it either. While critics may be enamored with its supposed artistry, many find it self-indulgent, emotionally hollow, and ultimately exhausting. What frustrates me the most is the way the film positions itself as profound while saying nothing particularly new. We’ve seen this kind of misery porn before—the kind that mistakes bleakness for depth, that assumes suffering alone makes a story meaningful. But suffering without complexity is just exploitation, and The Brutalist falls squarely into that trap.

Maybe in the hands of someone with a personal stake in the immigrant experience, The Brutalist could have been something more. Instead, it’s a self-congratulatory exercise in suffering, designed to impress rather than illuminate. And judging by the rapturous reviews and awards, Corbet pulled it off. But for me, The Brutalist isn’t just overrated—it’s a missed opportunity to tell a richer, more layered story about what it truly means to build a life in a new world.

Here are 10 films that, in my opinion, show a stronger cinematic exploration of the immigrant experience than The Brutalist, in no particular order:

The Godfather Part II, directed by Francis Ford Coppola - Trailer

Minari, directed by Lee Isaac Chung - Trailer

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder - Trailer

El Norte, directed by Gregory Nava - Trailer

An American Tail, directed by Don Bluth - Trailer

Avalon (1990), directed by Barry Levinson - Trailer

Heaven’s Gate, directed by Michael Cimino - Trailer

The Namesake, directed by Mira Nair - Trailer

The Visitor (2007) directed by Tom McCarthy - Trailer

Under the Same Moon (La Misma Luna) directed by Patricia Riggen - Trailer

This makes me think of Coppola and MEGALOPOLIS a little bit, too. Both from the artist as a self-mythologizing figure, and their blinders-on focus to create their art their way, for whatever the cost, whatever the struggle, whatever the "sacrifice", mythologizing said sacrifice and making it part of the film's story, and being able to only engage philosophically on this level - even though the movie is ostensibly about more than this - because it's all they've ever really cared about.

This may be why older artists lose relevance over time. Not just because they see the world with eyes from a previous era, but because over time they become the embedded, the industry insider who's still trying to play the suffering outsider, and it's THAT inauthenticity that comes through, too. Someone made this exact point about Tim Burton - you can only play the misunderstood goth outcast when you're not part of the fully accepted mainstream. And when you become the latter but keep trying to make the same movies with the same messages? It doesn't really work.

Spot on review. Hated this movie for all the reasons you perfectly articulate